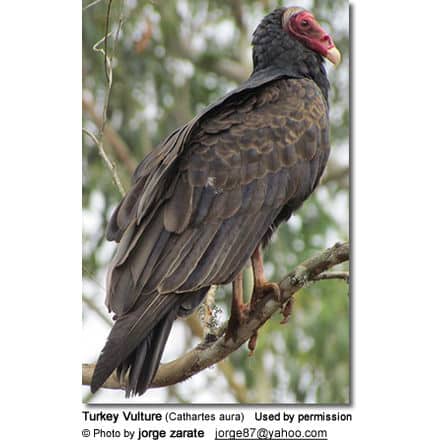

Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura)

The Turkey Vulture (Cathartes aura) is the most common vulture in the Americas. Despite the similar name and appearance, this species is unrelated to the Old World vultures in the family Accipitridae (which includes eagles, hawks, kites and harriers). The American species is a New World vulture in the family Cathartidae.

Recently, DNA evidence has shown that Turkey Vultures and other New World vultures are even more distantly related to Old World vultures than previously thought, and are now placed in Ciconiiformes, and are thus more closely related to storks than they are to Old World vultures. The similarities are due to convergent evolution.

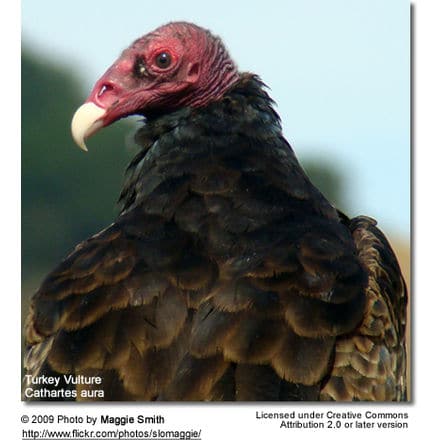

This bird got its common name because the adult’s bald red head was thought to resemble that of a male Wild Turkey.

Description

The typical adult bird is an average 76 cm (30″) long with a 185 cm (6 ft) wingspan, and weighing 1.4 kg (2.2 lb).

Both sexes appear similar with the female being slightly larger. Their body feathers are mostly brownish-black, but the flight feathers on wings appear silvery-gray underneath, contrasting with the darker wing linings.

The adult head is small in proportion to its body, red in color with little to no feathers on it, and has a relatively short, hooked bill that is ivory-colored.

There are five subspecies of Turkey Vulture:

- C. a. aura is the nominate subspecies. It is found from Mexico south through South America and the Greater Antilles. This subspecies occasionally overlaps its range with other subspecies. It is the smallest of the subspecies but is nearly indistinguishable from C. a. meridionalis in color.C. a. jota, the Chilean Turkey Vulture, is larger, browner, and slightly paler than C. a. ruficollis. The secondary feathers and wing coverts may have gray margins.C. a. meridionalis, the Western Turkey Vulture, is a synonym for C. a. teter. C. a. teter was identified as a subspecies by Friedman in 1933, but in 1964 Alexander Wetmore separated the western birds, which took the name meridionalis, which was applied earlier to a migrant from South America. It breeds from southern Manitoba, southern British Columbia, central Alberta and Saskatchewan south to Baja California, south-central Arizona, and south-central Texas. It is the most migratory subspecies, migrating as far as South America, where it overlaps the range of the smaller C. a. aura. It differs from the Eastern Turkey Vulture in color, as the edges of the lesser wing coverts are darker brown and narrower.C. a. ruficollis is found in Panama south through Uruguay and Argentina. It is also found on the island of Trinidad. It is darker and more black than C. a. aura, with brown wing edgings which are narrower or absent altogether. The head and neck are dull red with yellow-white or green-white markings. Adults generally have a pale yellow patch on the crown of the head.C. a. septentrionalis is known as the Eastern Turkey Vulture. The Eastern and Western Turkey Vultures differ in tail and wing proportions. It ranges from southeastern Canada south through the eastern United States. It is less migratory than C. a. meridionalis and rarely migrates to areas south of the United States.

Distribution and Habitat

The Turkey Vulture has a large range, with an estimated global occurrence of 28,000,000 km². It is the most abundant vulture in the Americas. Its global population is estimated to be 4,500,000 individuals.

It is found in open and semi-open areas throughout the Americas from southern Canada to Cape Horn. It is a permanent resident in the southern United States, though northern birds may migrate as far south as South America.

The Turkey Vulture is widespread over open country, subtropical forests, shrublands, deserts, and foothills.

It is also found in pastures, grasslands, and wetlands. It is most commonly found in relatively open areas which provide nearby woods for nesting and it generally avoids heavily forested areas.

Often, small to large groups of these birds spend the night at communal roosts. Favored locations may be reused for many years.

Summer Range

Breeds from southern Canada throughout the United States and southward through southern South America and the Caribbean. Local or absent in Great Plains.

Winter Range

Winters from northern California, Mexican border, eastern Texas, southern Missouri, and southern New York southward throughout the southeastern United States.

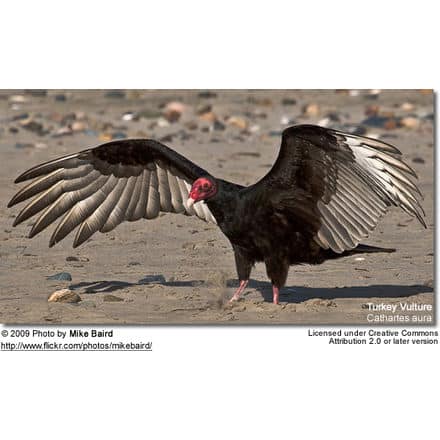

Flight

While soaring, they hold their wings in a V-shape and often tip “drunkenly” from side to side, sometimes causing the gray flight feathers to look silvery as they catch the light. They flap their wings very infrequently, and often take advantage of rising thermals to keep them soaring.

The flight style, small-headed and narrow-winged silhouette, and underwing pattern make this bird easy to identify at great distances.

These birds soar over open areas, watching for dead animals or other scavengers at work. Unlike most other birds, in addition to eyesight, the Turkey Vulture uses its sense of smell to locate dead animals.

It will often fly low to the ground to pick up the scent of mercaptan, a gas produced by the beginnings of decay of dead animals.

The part of its brain responsible for processing smells is particularly large, compared to other birds. Its heightened ability to detect odors allows it to find dead animals below a forest canopy.

Voice

Turkey vultures, like most other vultures, have very few vocalization capabilities. With no vocal organ, they can only utter hisses and grunts. They usually hiss when they feel threatened. Grunts are commonly heard from hungry young, and adults in courtship.

Diet

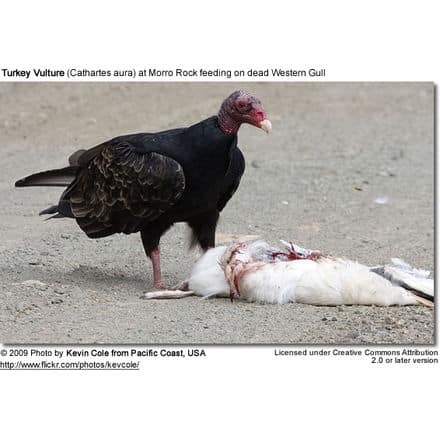

Feeds primarily on a wide variety of dead animals, from small mammals to dead cows, preferring those recently dead (fresh dead animals). Can also feed on plant matter, shoreline vegetation, pumpkin, crops, live insects, and other invertebrates.

They also prefer the meat of herbivorous animals, avoiding that of dogs and other carnivores. Turkey Vultures can often be seen along roadsides, cleaning up roadkill, or near rivers, feasting on washed-up fish, another of their favorite foods.

Breeding / Nesting

The breeding season of the Turkey Vulture commences in March, peaks in April to May, and continues into June. Courtship rituals of the Turkey Vulture involve several individuals gathering in a circle, where they perform hopping movements around the perimeter of the circle with wings partially spread. In the air, one bird closely follows another while flapping and diving.

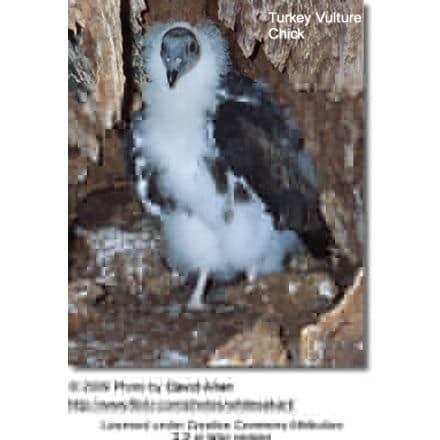

Eggs are generally laid in the nesting site in a protected location such as a cliff, a cave, a rock crevice, a burrow, inside a hollow tree, or in a thicket. There is little or no construction of a nest; eggs are laid on a bare surface.

Females generally lay two eggs, but sometimes one and rarely three. The eggs are cream-colored, with brown or lavender spots around their larger end. Both parents incubate, and the young hatch after 30 to 40 days.

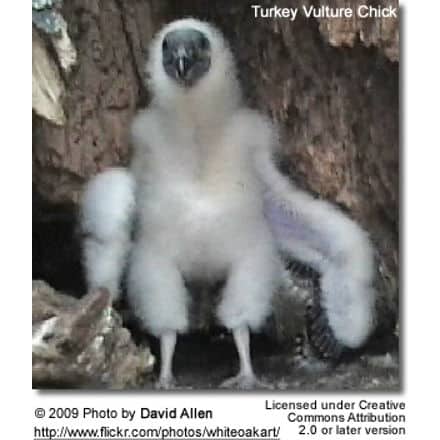

Chicks are altricial, or helpless at birth. Both adults feed the chicks by regurgitating food for them, and care for them for 10 to 11 weeks. When adults are threatened while nesting, they may flee, or they may regurgitate on the intruder or feign death.

If the chicks are threatened in the nest, they defend themselves by hissing and regurgitating. The young fledge at about nine to ten weeks. Family groups remain together until fall.

Behavior

The Turkey Vulture is gentle and non-aggressive. Turkey Vultures roost in large community groups, breaking away to forage independently during the day.

Turkey Vultures are often seen standing in a spread-winged stance. This is called the “horaltic pose.” The stance is believed to serve multiple functions: drying the wings when it rains, warming the body, and baking off bacteria.

The turkey vulture has few natural predators. Its primary form of defense is vomiting. The birds do not “projectile vomit,” as many would claim. They simply cough up a lump of semi-digested meat.

This foul smelling substance deters most creatures intent on raiding a vulture nest. It will also sting if the offending animal is close enough to get the vomit in its face or eyes.

In some cases, the vulture must rid its crop of a heavy, undigested meal in order to lift off and flee from a potential predator. In this case, the regurgitated material has not yet been digested. Most predators will give up pursuit of the vulture in favor of this free edible offering.

Like its stork relatives, the Turkey Vulture often defecates on its own legs, using the evaporation of the water in the feces and/or urine to cool itself down, a process know as urohydrosis.

Also, due to the nature of their diets, vulture excreta has a high uric acid content that acts as a sanitizer and kills any bacteria the bird picks up while traipsing on its food.

This allows them to be very tolerant of microbial toxins, such as botulism, and certain synthetic poisons that have been used to kill coyotes and ground squirrels.

Protection status

In the United States, this species receives special legal protections under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. Overall North American populations have increased over the last few decades and the breeding range has expanded northward.

Interesting facts

The Turkey Vulture usually forages alone, unlike its smaller, more social relative, the American Black Vulture.

Although one Turkey Vulture can dominate a single Black Vulture at a carcass, usually such a large number of Black Vultures appear that they can overwhelm a solitary Turkey Vulture and take most of the food.

Circling vultures do not necessarily indicate the presence of a carcass. Circling vultures may be gaining altitude for long flights, searching for food, or playing.

A group of vultures is called a “Venue”. Vultures circling in the air are a “Kettle”

Vultures have excellent eyesight, but, like all other birds, they have poor vision in the dark.

This bird is said to be the most damaging bird to aircraft in birdstrikes as rated by the Smithsonian Institution’s Feather Identification Laboratory.

As of July’s 2006 planned launch of the Space Shuttle Discovery STS-121 mission, NASA is taking actions to prevent any vultures and other birds from striking the shuttle during liftoff, as it can possibly present certain threat of damaging the vehicle.