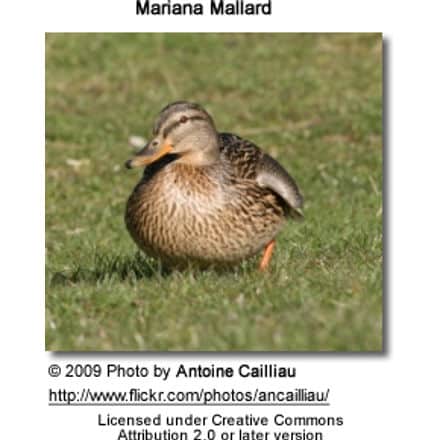

Mariana Mallards

The Mariana Mallards (Anas oustaleti) or Oustalet’s Gray Duck is an extinct species of duck of the genus Anas that was endemic to the Mariana Islands. It is sometimes treated as a subspecies of the Mallard or the Pacific Black Duck, or (erroneously) the Spot-billed Duck (as Anas poecilorhyncha oustaleti).

This species is an interesting example of speciation by hybridization (which is very rare in birds and mammals), as it is apparently derived from migrating individuals of the Mallard (A. p. platyrhynchos) and the Australasian Black Duck (A. s. rogersi) which settled down and became resident on the Marianas. The speciation process has only started in comparatively recent time (thousands of years maybe) and neither Mariana Mallards nor their progenitor species are known from fossils on the Marianas, casting into doubt the assumption that a resident Black Duck population had been long established on the islands. A species of flightless duck known from a prehistoric bone found on Rota in 1994 (Steadman, 1999) was apparently not closely related to the Recent birds.

The IUCN, among others, does not consider the Mariana Mallard a proper species yet and thus does not include it in its redlist. However, as the population constituted a distinct, established and independent evolutionary unit (although not yet phenotypically homogenized), it was at least an incipient species. If considered specifically distinct, it was one of the most short-lived vertebrate species known to science, existing for a few 10.000 years at most from the fist hybridization event to its extinction.

Local names are ngånga’ (palao) in Chamorro and ghereel’bwel in Carolinian. The binomial of this species commemorates the French zoologist Emile Oustalet.

Description

Mariana Mallards were 51-56 cm long and weighed approximately one kilogram, making them marginally smaller than mallards. Two intergrading color morphs were found in males, called the “platyrhynchos” and the “superciliosa” type after the species they resembled more.

Only the former had a distinct nuptial (breeding) plumage: the head was green as in mallard drakes, but less glossy, with some buff feathers on the sides, a dark brown eyestripe and a faint whitish ring at the base of the neck. The upper breast was dark ruddish chestnut brown with blackish-brown spots. The wing patch (speculum (= distinctive wing patch ) and the tail was also like in mallard drakes’ nuptial plumage, including curled-up central tail feathers, but the tips of the speculum (= distinctive wing patch) feathers were buff. The underside was a mix between the vermiculated grey feathers of the mallard and the brown ones of the Pacific Black Duck. The remainder of the bird looked like a male Pacific Black Duck with lighter underwings. The bill was black at the base and olive at the tip, the feet reddish orange with darker webs and the iris brown. The eclipse plumage looked similar to a dark eclipse mallard drake.

Males of the “superciliosa” type resembled an Island Black Duck with a less distinctly marked head, the supercilium (line above eye) and cheeks being buffy and the cheek (malar) stripe hardly visible. The upper breast, flank and scapular feathers had broader buff edges, and the underwings were lighter. The speculum (= distinctive wing patch) was usually as in the “platyrhynchos” type, i.e. mallard-like, but at least two specimens have the green speculum of the Pacific Black Duck. The bill was like that of A. superciliosa, and the iris and legs similar to the “platyrhynchos” type.

Females looked essentially like a dark mallard female with the orange of the feet and near the bill tip usually a bit more pure.

Ducklings were probably intermediate in plumage between the two progenitor species, somewhat duller than mallard or somewhat more vivdly colored than Pacific Black Duck downy young.

Call / Vocalization

The voice can be assumed to have resembled the Mariana Mallards parent species’; possibly, the females’ quacking was hoarser than in the mallard.

Distribution

It occurred, in recent times at least, on the islands of Guam, Saipan and Tinian. Madge and Burn (1988) mention a report of 2 unidentified ducks seen on Rota in 1945, but as no movement of A. oustaleti between Saipan and Tinian, which are just 8 km apart, was recorded (Kuroda, 1941-42), these were probably vagrant migrating ducks, although Marshall (1949) suspected from circumstantial evidence that such movement did indeed take place. However, the distance between Guam and Rota is nearly 80 km, making intentional migration between these islands not likely.

Ecology

The Mariana Mallards inhabited wetlands, mostly inland but occasionally also in coastal areas. On Guam, it was most abundant in the Talofofo River valley, on Tinian on Lake Hagoi and Lake Makpo (now Makpo Swamp) before it was drained, and on Saipan on the Garpan lagoon and on and around Lake Susupe. The birds were rather reclusive, preferring sheltered habitat with plenty of wetland/water plants – fern Acrostichum aureum thickets and Scirpus, Cyperus and Phragmites (australis) karka reed beds, as described in detail by Tenorio et al. (1979) and Stemmermann (1981) -, where they also nested. Usually, pairs or small flocks were encountered, but in the key habitats larger groups of dozens and rarely up to 50-60 individuals could be found. Apart from possible inter-island movement, the birds were not migratory.

Feeding and reproduction is not well documented, but cannot expected to differ significantly from its immediate relatives: The birds fed on aquatic invertebrates, small vertebrates and plants and although up-ending was not observed, they probably utilized it too.

Breeding was recorded from at least January to July, with a peak in June/July at the end of the dry season. One male specimen taken in October was also in breeding condition (Marshall, 1949); thus, the birds may have bred nealy year-round at least on occasion. Unfortunately, the courtship behavior, which in the strongly sexually dimorphic mallard is focused more on presentation of visual cues than in the monomorphic Pacific Black Duck (although it is generally similar in both species), was never recorded. The clutch consisted of 7-12 pale grey-green oval eggs measuring 61.6 x 38.9 mm on average (Kuroda, 1941-42). Males took no part in incubation, which lasted around 28 days, and caring for the ducklings. The young fledged when c. 8 weeks old and became sexually mature the following year.

Extinction

The birds declined due to draining of wetlands for agriculture and construction. Hunting pressure was probably heavy, despite a ban on gun ownership under Japanese control (1914-1945), as the birds were unwary to be trapped, and at any rate the gun ban was lifted after World War II (see also below). By the 1940s, flocks of more than a dozen birds were seldom seen. On Guam, the last sightings were in 1949 and 1967 – the latter being a single, possibly vagrant, bird – and on Tinian in 1974. As Lake Susupe offered the most plentiful and least accessible habitat, although it too suffered from pollution by sugar mill wastes, the Saipan population lingered on for a few more years. The Mariana Mallard was listed as federally endangered on June 2, 1977 (United States Government, 1977). In 1979, two males and a female were found on Saipan and caught; one male was later released, the last wild bird ever to be encountered. The pair was brought to Pohakuloa, Hawai‘i, and later to SeaWorld, San Diego, where it was attempted to have them reproduce in captivity. However, this was unsuccessful and the species became extinct with the death of the last individual in 1981. Surveys were conducted in the following years, but the species was certainly gone by then. It was removed from the USFWS Endangered Species List on February 23, 2004, due to extinction (United States Government, 2004).

Collection of specimens for museums and private collections must have had a temporary impact during the Japanese control over the islands. Although less than 100 specimens are on record, most were taken in the 1930s and 1940s for Japanese collectors; given the rather sedentary habits and small population size of the species, this may have jeopardized local populations to the point of extinction. Outside Japan, 7 specimens (including the type) are in the MNHN, Paris, one in the Walter Rothschild Zoological Museum, Tring, two in the USNM, Washington D.C. and six in the AMNH, New York City (FWIE-VTU, 1996). Greenway (1967) mentions additional specimens in Cambridge, Massachusetts and Lisbon.

“New Zealand Mallard”

The evolutionary lineage of the Mariana Mallards was terminated by its extinction. However, a similar hybrid population is found in many locations of New Zealand, particularly around urban areas. The parents of these hybrids are the native New Zealand Black Ducks and introduced mallards which spread with increasing land clearance after the 1950s. In some areas, hybrids make up over half the population by now (Gillespie, 1985). According to Rhymer et al. (1994), “[t]he speciation process appears to be undergoing reversal.” Their study shows that the more colorful mallards drakes, somewhat surprisingly, contribute less to the gene pool. In dabbling ducks, speciation is mainly driven by behavioral and morphological cues, namely the drakes’ plumage and courtship displays, and the females’ vocalizations. Many Anas species probably separated less than 100.000 years ago, and with hybridization not infrequent among these ducks, molecular barriers eliminating gene flow have not yet become established. The cases of the Mariana Mallards and the New Zealand hybrids illustrate well how under certain circumstances even the behavioral barriers may break down. It could be said that these cases represent evolution running at the same time both “backwards” – as separated species merge again – and “forward” – as a distinct new lifeform is produced in this process, which does probably not resemble the mid-/late Pleistocene mallard/Pacific black duck common ancestor, and certainly is not equivalent to it genetically because of the evolutionary changes both species have undergone since their separation.

Copyright: Wikipedia. This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from Wikipedia.org.

Relevant Resources

Please Note: The articles or images on this page are the sole property of the authors or photographers. Please contact them directly with respect to any copyright or licensing questions. Thank you.