Common Poorwill

The Common Poorwill, Phalaenoptilus nuttallii, is the smallest member of the North American nightjar family. It is related to the nighthawks.

Even though, the Common Poorwill is fairly common in western parts of the United States, it is rarely seen as it is only active at night (nocturnal).

The Common Poorwill is considered the western counterpart of the related and similar eastern Whip-poor-will – in fact, in the past, these two were considered a single species.

Its scientific name “nuttallii” honors the English-born American ornithologist Thomas Nuttall.

Hibernation

The Common Poorwill has gained fame as the first bird species KNOWN to hibernate for weeks or even months under natural conditions. One individual was recorded to remain in hibernation for at least 85 days for the 1947 to 1948 season (Jaeger, 1949).

However, the first ones to be aware of this species’ behavior appear to have been the Native Americans of the Hopi tribe as they referred to the Common Poorwill as “The Sleeping One”.

Common Poorwills can enter hibernation in response to environmental stress (lack of food and / or inclement weather).

Most populations occurring on the southern edge of this species’ range in the United States enter hibernation, with reports from California, New Mexico and as far north as North Dakota (Meriwether Lewis, 1804). The northern populations typically migrate south to winter in warmer climates rather than hibernating.

When hibernating, they typically hide away in rocky crevices for several weeks (mostly winter time) and emerge in spring when the temperature has risen and food (insects) are readily available.

Hibernation has also been induced in captive specimens by withholding food and decreasing the environmental temperature. Researchers found that they would come out of hibernation when the room temperature increased to as low as 10 degrees Celsius (50 degrees Fahrenheit) (Howell and Bartholomew, 1959; Jaeger, 1949; Withers, 1977).

Hibernation involves slowing the metabolic rate, dropping the body temperature down dramatically and a slowing heart rate. This allows a bird to go without food for extended periods and survive cold spells.

However, it is entirely possible – although not officially proven – that other members of the typical Nightjar family (caprimulgids) also hibernate.

Other bird species go into “temporary hibernation” — also commonly referred to as “torpor” – which is not as deep as true hibernation and only lasts for shorter periods (generally overnight or when food is scarce).

Birds that are known to enter a state of “semi-hibernation” or “suspended animation” on a regular basis, include hummingbirds, mousebirds, manakins,and swifts.

Distribution / Range

Common Poorwills are mostly migratory birds that are native to Canada, United States and Mexico.

They summer throughout the western half of the United States and Canada, and migrate south to winter in the extreme southwestern United Statesand Mexico.

In Southwestern United States, they may occupy the same region year round but migrate to higher elevations for the breeding season and to lower elevations during the winter. (Alderfer, 2006; Csada and Brigham, 1992; Dunne, 2006). They may enter the state of hibernation to survive cold spells.

Their breeding (summer) range includes southeastern and south central British Columbia, Alberta, southwestern Saskatchewan through to southeastern Montana, central Texas and southwestern United States, as well as southern Baja California Mexico.

Most of them arrive in their breeding territory in April to May. The Southern populations arrive for breeding season from February to March.

Wintering range: From September to November, the northern populations migrate south to winter in southwestern USA (central California and southern Arizona), southern Texas (south central USA) and south, central and western Mexico. The southern populations leave in October to November for their winter range.

The time of migration could occur a month earlier or later – depending on weather conditions and the range they occupy.

Their population density is higher at their southern range, with Arizona showing a density of 0.43 to 0.49 birds per survey station; but only 0.13 birds per survey station in British Columbia and Saskatchewan (Csada and Brigham, 1992; Csada and Brigham, 1994; Hardy et al., 1998).

Subspecies and Ranges

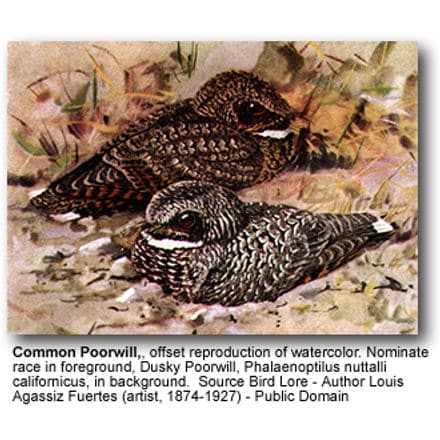

Six subspecies are described based mostly on geography (although the winter ranges seem to overlap) and some show plumage differences.

However, some argue that light and dark morphs exist throughout its range, making differentiation between the subspecies and morphs challenging, which justifies additional genetic research to verify the existence of subspecies (Alderfer, 2006; Csada and Brigham, 1992; Csada and Brigham, 1994; Dunne, 2006; Thomas, Brigham, and Lapierre, 1996)

- Common Poorwill – Phalaenoptilus nuttallii nuttallii (Audubon, 1844)

- Range: Breeds in North America, specifically Southwestern Canada south through western and central western USA to northern Mexico

- Dusky Poorwill – Phalaenoptilus nuttallii californicus (Ridgway, 1887)

- Range: Western California (USA) and northern Baja California (Mexico)

- ID: Darker and browner plumage than the nominate race

- Desert Poorwill – Phalaenoptilus nuttallii hueyi (Dickey, 1928)

- Range: Southeastern California, southwestern Arizona (USA) and northern Baja California (Mexico)

- ID: Paler plumage than the nominate race. It occurs in southern California.

- San Ignacio Poorwill – Phalaenoptilus nuttallii dickeyi (Grinnell, 1928)

- Range: Resident in Southern Baja California in Mexico

- ID: Smaller and less heavily marked than the Californian Dusky Poorwill

- Sonoran Poorwill – Phalaenoptilus nuttallii adustus (van Rossem, 1941)

- Range: Extreme southern Arizona south to central Sonora (northern Mexico)

- ID: Paler and browner plumage than the nominate race

- halaenoptilus nuttallii centralis (R. T. Moore, 1947)

- Range: The most southern race occurs in Central Mexico

Habitat

Throughout their range, Common Poorwills occur in climates with extreme temperature variances – from desert flats to mountain foothills up to elevations of 500 up to 2,500 m (1,640 to 8202 ft), and occasionally even higher (Csada and Brigham, 1992; Dunne, 2006; Hardy et al., 1998; Wang and Brigham, 1997).

They are mostly found in dry, open, grassy or shrubby areas (arid or semi-arid habitats), such as shrub steppe, rocky / desert canyons, stony desert slopes with very little vegetation, open woodlands, as well as dry, open or broken forests (rarely in the interior of forests). They frequent valleys and foothills.

They prefer vegetation of short grasses, shrubs, as well as deciduous or coniferous growth. Trees or shrubs are usually found close to their nesting or roosting sites, such as white fir, ponderosa pine, trembling aspen, Jeffrey pine and creosote.

Roost sites are usually close to the bare ground, and tend to be open with little live vegetation cover.

Its nocturnal lifestyle and camouflaging plumage makes this bird difficult to find. In most cases, it is spotted at night sitting on dirt roads when their eyes reflect in car headlights.

Description

Common Poorwills are medium-sized birds with an adult length of 18 to 21 cm (7 – 8.3 inches) – from top of the head to tail.

The wingspan is 42.7 to 44.1 cm (~ 17 inches). They weigh 42.8 – 58.1 g (1.51 to 2.05 oz); the average weight being 51.6 g (1.8 oz).

The females tend to be slightly larger than the male. The weight differs amongst the populations and the time of the year. The males usually lose weight early on in the breeding season, and both genders gain weight prior to migration.

The Common Poorwill has a large head, a very small bill and tiny feet that are rarely seen. The bill is short and wide with a large open gape and pronounced bristles extending laterally from the base.

They have large eyes that allow them to see in low light conditions. In flight, their short rounded wings can best be observed. The tail is short and also rounded.

The plumage is light brown mottled with grey, brown, black and white patterns. It has a white band across the throat. The under plumage is narrowly barred. The outer tail feathers are dark tipped with white.

Gender Identifications

Females are slightly larger. The outer tail-feathers are tipped white and more conspicuously in the male and buff-colored in the female.

Immature

Juveniles resemble the adults.

Similar Species

- Nighthawks are a little larger, have a longer tail and longer, thinner wings – compared to the Common Poorwill which has more rounded wings and no white bar. Nighthawks have longer tails compared to the Common Poorwill which has a short, rounded tail with white corners. The Poorwill has a thicker white throat patch.

- The Common Poorwill can also be identified by its call from which its name was derived — it is a monotonous poor-will or poor-will-ow sound that is mostly given from dusk to dawn.

Nesting / Breeding

Northern populations breed from late May to September and those in the southern regions typically breed from March to August.

At the beginning of the breeding season, the males establish territories that they aggressively defend against other males. It has been suggested that the northernmost return to the same breeding area over consecutive seasons. Pairs are monogamous over a single breeding season.

The Common Poorwills don’t actually build a nest. They only make a shallow depression in the soil. The nesting site is often partially shaded by nearby shrubs, clumps of grass, rocks or fallen trees. Although they are sometimes placed at the base of a hill or in a secluded rock shelter.

Common poorwill pairs typically lay the first clutch soon after arrival in their breeding range. If conditions are good, they will raise a second brood towards the end of the breeding season.

The second nest is usually located within 100 m (330 feet) of the first nest. The male will continue to take care of the first young, while the female incubates the second clutch.

A clutch usually consists of two eggs laid over two consecutive days. The eggs are white to creamy or pinkish – sometimes with darker mottling.

Both parents share the incubation duties; although the male is often more likely to incubate eggs during the daytime. At night, the eggs or any nestlings may be left for short periods while the parents hunt.

The eggs are incubated for 20 to 21 days. The hatchlings weigh about 4 g (0.14 oz) and are covered in feathers.

Unlike most other bird species, their eyes are already open. After hatching, the female is more likely to brood nestlings during the daytime than the male. Both parents feed the young a diet of regurgitated insects.

The parents limit their daylight movements and rely on their camouflaging plumage to keep the nest hidden from predators.

The nesting parents are very protective and will growl or hiss at those that approach the nest (not unlike, and potentially imitating, a snake). They may fluff their feathers and elevate their wings to make themselves look bigger in an attempt to intimidate intruders.

However, if an intruder comes within 1 meter or 3 feet, they usually flush from the nest and attempt to distract predators away from the nest. They may pretend to be injured, thus making predators believe that they are an easy prey.

They may move the eggs and nestlings a short distance (1 – 3 meters or 3 – 10 feet) away from the original nest if they feel that the original location is no longer secure.

The young leave the nest when they are about 20 to 23 days old, but will still receive parental care for another three weeks before they are completely independent.

What sets the Common Poorwill apart from just about all other bird species is the fact that they can go into torpor (hibernation) while incubating eggs.

This may be caused by a cold spell, for example, or potentially lack of food. This allows them to save parental energy. This will, however, reduce egg viability and often results in higher rates of nest abandonment.

Diet / Feeding

Common Poorwills feet exclusively on insects, mostly moths and beetles – which make up about 90% of their diet (determined by analysis of fecal pellets).

Additionally, they take grasshoppers, locusts and other mostly night-flying insects. Insects that are up to 1.5?or 4 cm long are usually swallowed whole. Most of the insects they eat are between 5 – 7 mm (0.2 – 0.28 inches) long.

It is estimated that Common Poorwills make 200 to 300 flights per night to obtain a minimum of 9.7 grams or 0.34 ounces of insects needed to maintain their weight. Like owls, the Common Poorwills eject indigestible parts.

They are often observed foraging from low perches flying up to catch insects mid-air (usually flying no more than 3 meters or 10 feet high into the air).

On some rare occasion, they may chase insects for a while – although the vast majority of flights last only about three seconds before they return to their perch or ground. They may also pick insects off the ground (such as spiders).

Their large eyes are well adapted for low light conditions and the large gaping mouth allows them to more easily capture insects in mid-air.

They usually feed near dawn and dusk, or on moonlit nights, when the sky is light enough for them to spot flying insects by silhouette.

They often drink on the wing, swooping down to skim the water’s surface with the open bill.

Vocalizations / Communication

The Common Poorwill has melancholy poor-WILL-ip or poor-WILL-ow song, for which this species has been named. The second note is higher in pitch and the third syllable is only audible at close range. The song is in the 1.5 kHz range. In flight, they utter a low wurt, wurt or chuck notes.

Both males and females vocalize similarly, however, the females less frequently. During the mating season, the males increase the frequency and duration of calling to advertise their presence in a territory and to attract females.

In addition to the calls, wing clapping has been reported in one instance (Mengel, Sharpe and Woolfenden, 1972); however, it has not been established whether this method of communication was used for courtship or territorial defense.

This noctural species is best known from its night cries that sound as they called out their names again and again: poor-WILL, poor-WILL, poor-WILL, poor-WILL or – when the listeners are close, they may hear repeated: poor-WILL-ow, poor-WILL-ow, poor-WILL-ow, poor-WILL-ow.

Behavior

During the daytime, Common Poorwills usually roost on the ground, in rock crevices or on low-hanging limbs. They may roost alone or individuals may be found roosting together.

Their flight is usually close to the ground and is described as moth-like flutters followed by a smooth glide.

After landing, Common Poorwills have been observed holding their wings vertically for 5 to 10 seconds before snapping them back into folded position – the reason for which is unknown.

Lifespan / Longevity

In the wild, their maximum recorded lifespan is at least 3 years. Captive specimens did not adapt well to human care and died prematurely.

Both the male and the female reach reproductive maturity when they are about one year old.

Status / Conservation and Predation

Common Poorwills have an extremely large range and are not considered endangered.

In fact, its population appears to be increasing, probably as they benefited from human activities, such as cattle grazing or logging, which created the open habitats they thrive in (Csada and Brigham, 1992).

Therefore, the status of this species is evaluated as Least Concern.

However, as ground dwellers, they are easy prey and losses due to predation can be high. They are commonly predated upon by birds of prey, owls, coyotes, cats, dogs, American badgers, foxes, skunks and snakes.

They have developed several behavioral adaptations to minimize predation:

- Their nocturnal (night) lifestyle reduces the likelihood of being detected by daytime predators. During the daytime, they typically sleep on the ground where they are perfectly camouflaged by their “earthy” colored plumage. They almost always change their roost sites on a daily basis.

- When nesting, they sit quietly on the eggs, minimizing any movements that could get them detected.

- If an intruder does get close to the nest, the parents may try to lead them away by first flushing off the nest and when landing feigning injury as they lead the potential thread away from the nest. While the parent performs this distraction display, the young may scatter and freeze.

- The parent who is not incubating the eggs or brooding the young will roost away from the nesting area.

- They may also move the eggs or young to prevent them from being preyed upon.

- The Common Poorwills avoid voicing when they hear the calls made by predatory nocturnal animals, such as owls.

Alternate (Global) Names

Czech: Lelek americký

Danish: Amerikansk Poorwill

Dutch: Nuttall-nachtzwaluw, Nuttalls Nachtzwaluw, Poorwill

German: Poorwill, Winternachtschwalbe

English: Colorado Desert, Colorado Desert Poor-will, Desert Poor-will, Dusky Poor-will, Frosted Poor-will, Nuttall’s Poor-will, Nuttall’s Whip-poor-will …

Estonian: uni-öösorr

Finnish: Horroskehrääjä

French: Engoulevent de Nuttall

Italian: Succiacapre di Nuttall

Japanese: puaawiruyotaka, pua-wiruyotaka

Norwegian: Dvalenattravn

Polish: Lelek zimnodr?tw, lelek zimowy

Slovak: lelek spác, Lelek spá?

Spanish: Pachacue común, Chotacabras Pachacua, Pachacua Norteña, tapacamino tevií, Tapacamino Tevíi

Swedish: Dvalnattskärra