White-tipped Sicklebills (Eutoxeres aquila)

The White-tipped Sicklebills (Eutoxeres aquila) are hermits with a natural range that stretches from Costa Rica in Central America to Northern Peru in Southern America.

Subspecies

Eutoxeres aquila aquila (Bourcier, 1847) – Nominate Race

- Eutoxeres aquila heterurus Gould, 1868Eutoxeres aquila salvini Gould, 1868

Alternate (Global) Names:

Spanish: Picohoz Coliverde; French: Bec-en-faucille aigle; Italian: Colibrì beccodifalce codabronzata; German: Weißkehl-Sichelschnabel; Czech:kolib?ík orlozobec;Danish:Hvidspidset Seglnæbskolibri; Finnish: viherkoukkukolibri; Japanese: kamahashihachidori; Dutch: Haaksnavelkolibrie; Norwegian: Grønnsigderemitt; Polish: orlodziobek ciemnosterny; Slovak: srpozobec škvrnitý; Swedish: Örnkolibri

Distribution / Range

The White-tipped Sicklebills are found in Costa Rica and Panama of Central America; as well as Colombia, Ecuador, and far northern Peru in South America. There is one recent record exists from Mérida in Venezuela.

They are typically found in the understory of humid forests in foothills on mountain slopes, and along forest borders.

Description

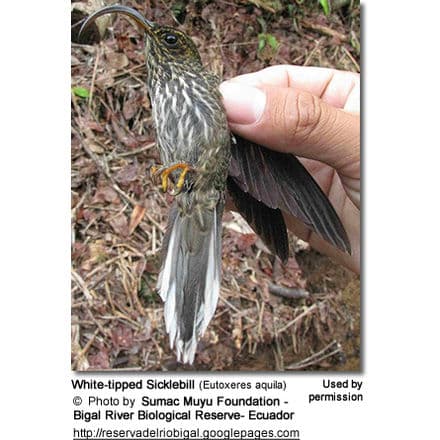

The White-tipped Sicklebills average 5.5 inches or 13.97 cm in length (measured from the tip of the bill to the end of the tail).

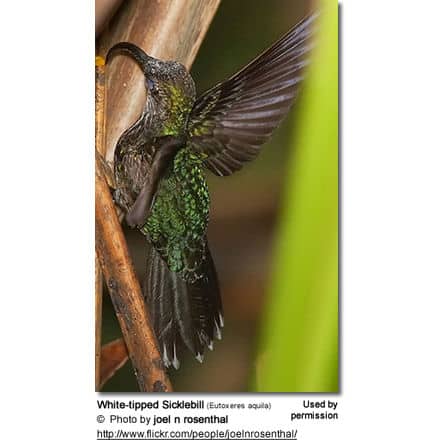

This species can easily be distinguished from all other hummingbirds by its sharp and extremely curved bill, bending almost to a right angle. The upper bill is black and the lower bill is yellow.

Its upper plumage is green and the under plumage is striped white. The tail is a glossy dark green with a white tip.

Calls / Vocalizations

The White-tipped Sicklebill makes low-chip notes while traveling between feeding sites.

Nesting / Breeding

Hummingbirds are solitary in all aspects of life other than breeding, and the male’s only involvement in the reproductive process is the actual mating with the female. They neither live nor migrate in flocks, and there is no pair bond for this species.

Males court females by flying in a U-shaped pattern in front of them. He will separate from the female immediately after copulation. One male may mate with several females. In all likelihood, the female will also mate with several males. The males do not participate in choosing the nest location, building the nest, or raising the chicks.

The female White-tipped Sicklebill is responsible for building the remarkable cone-shaped nest (with an approx. diameter of around 2 inches or 50 mm) which hangs by a single strong string of spiders’ silk and/or rootlets from some overhead support, which could be a branch or the underside of the broad leaves of, for example, Heliconia plants, banana trees or ferns about 3 – 6 ft (1 – 2 m) above ground.

However, these unusual nests have been found beneath bridges, in highway culverts and even hanging from roofs inside dark buildings. The nest is often near a stream or waterfall.

It is constructed out of plant fibers woven together and green moss on the outside for camouflage in a protected location.

She lines the nest with soft plant fibers, animal hair, and feathers down, and strengthens the structure with spider webbing and other sticky material, giving it an elastic quality to allow it to stretch to double its size as the chicks grow and need more room.

The average clutch consists of two elliptical white eggs, which she incubates alone, while the male defends his territory and the flowers he feeds on. The young are born blind, immobile, and without any down.

The female alone protects and feeds the chicks with regurgitated food (mostly partially digested insects since nectar is an insufficient source of protein for the growing chicks). The female pushes the food down the chicks’ throats with her long bill directly into their stomachs.

As is the case with other hummingbird species, the chicks are brooded only the first week or two and are left alone even on cooler nights after about 12 days – probably due to the small nest size. The chicks leave the nest when they are about 20 days old.

Diet / Feeding

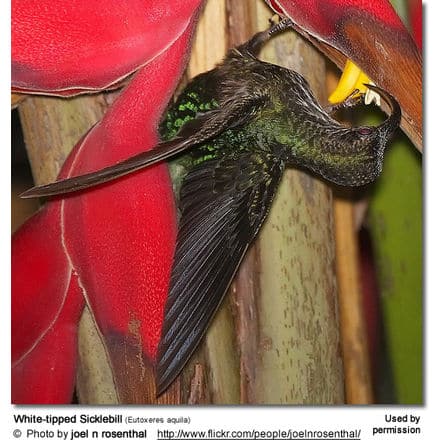

The White-tipped Sicklebills primarily feed on nectar taken from a variety of brightly colored, scented small flowers of trees, herbs, shrubs, and epiphytes. They favor flowers with the highest sugar content (often red-colored and tubular-shaped), such as the Heliconia, Centropogon, or Plantain flowers.

Hermits are “trap-line feeders”, as such they visit plants along a long route (in this case up to 0.6 miles or 1 km). This differentiates them from most other hummingbird species which generally maintain feeding territories in areas that contain their favorite plants (those that contain flowers with high-energy nectar), and they will aggressively protect those areas.

Hermits use their long, extendible, straw-like tongues to retrieve nectar while hovering with their tails cocked upward as they are licking at the nectar up to 13 times per second. On occasion, they may be seen hanging on the flower while feeding.

Many native and cultivated plants on whose flowers these birds feed heavily rely on them for pollination. The mostly tubular-shaped flowers exclude most bees and butterflies from feeding on them and, subsequently, from pollinating the plants.

They may also visit local hummingbird feeders for some sugar water, or drink out of bird baths or water fountains where they will either hover and sip water as it runs over the edge; or they will perch on the edge and drink – like all the other birds; however, they only remain still for a short moment.

They also take some small spiders and insects – important sources of protein particularly needed during the breeding season to ensure the proper development of their young. Insects are often caught in flight (hawking); snatched off leaves or branches, or taken from spider webs. A nesting female can capture up to 2,000 insects a day.

Males establish feeding territories, where they aggressively chase away other males as well as large insects – such as bumblebees and hawk moths – that want to feed in their territory. They use aerial flights and intimidating displays to defend their territories.

Metabolism and Survival and Flight Adaptions – Amazing Facts

Beauty Of Birds strives to maintain accurate and up-to-date information; however, mistakes do happen. If you would like to correct or update any of the information, please contact us. THANK YOU!!!