Collembola: The Deep-Cave Dwelling World of The Springtails

Collembola (Springtails)

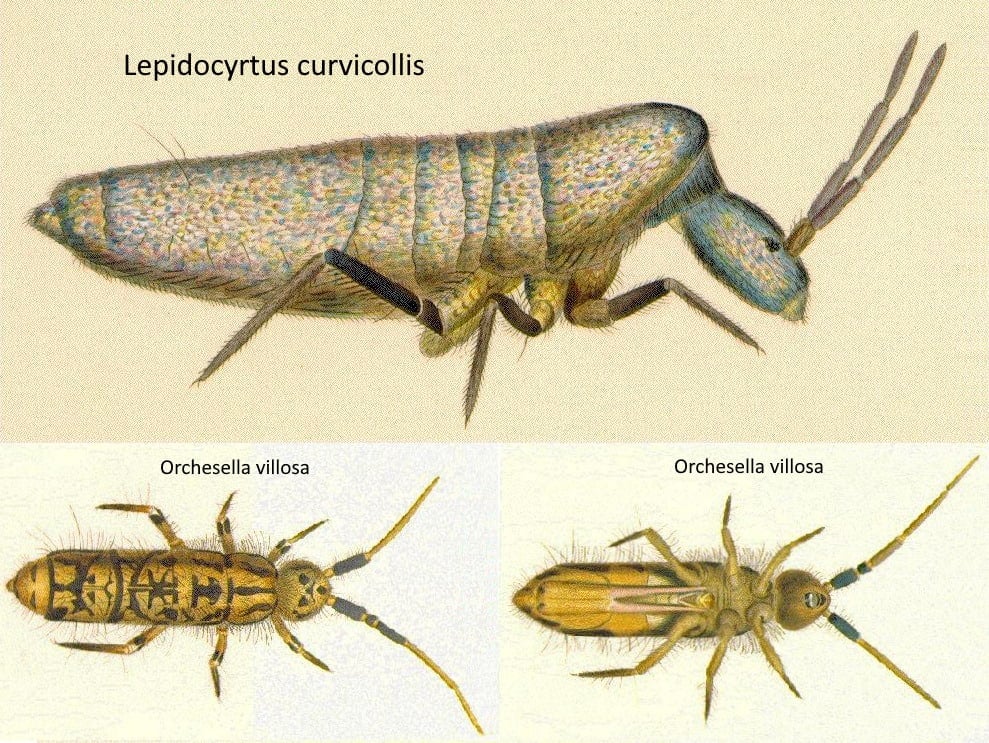

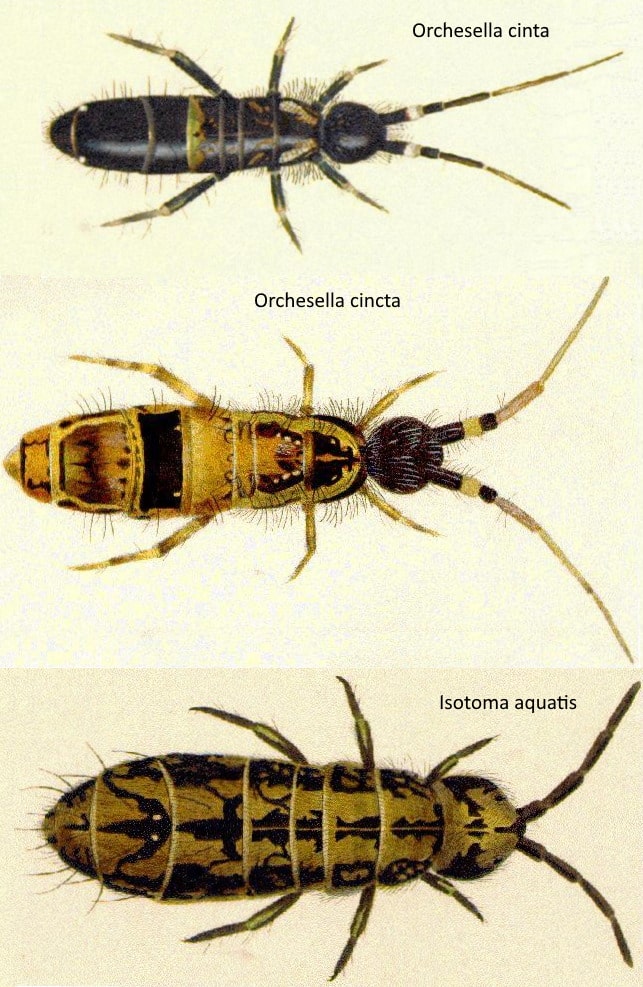

Collembola are small to minute hexapods, often clothed in coloured scales.

The antennae have less than 6 segments and the eyes are either simple ocelli or absent. The legs have only four segments the last being the tibiotarsus, they possess no wings. The abdomen possess’s only 6 segments;

On the first is the ventral tube. This is an organ for the absorption of moisture, from which the order derives its name: “kolla” = glue (in the mistaken belief that the ‘peg’ was used by the animal to glue itself to smooth surfaces) and “embolon” = a peg.

On the third is the minute retinaculum or hamula, which helps to hold the furca in place when it is held under the abdomen. And on the fourth is the ‘furca’ itself, this is a forked springing organ, from which the creature derives its common name of “springtail”.

They are not now considered to be insects by many authorities but are instead referred to as hexapods, making them a branch of the main stem that insects evolved from. Hexapods includes Collembola, Diplura, Protura and the Insecta – which in turn includes the rest of the insect orders.

In other words, all insects are hexapods but not all Hexapods are insects.

The name ‘Collembola’ was first given to the springtails by John Lubbock in 1871 in his monograph on the Collembola and Thysanura. Before that they were treated as part of the same order as Thysanura.

Collembola have been around at least 400 million years, the oldest known fossil Hexapod Rhyniella praecursor is a Collembola from chert of the Lower Devonian era.

There are more than 6,000 known species in the world and some people estimate that there may be as many as 50,000, making them very a successful group of hexapods. They live just about everywhere, in the canopy of tropical rain forests, on the beach, in tidal rock pools, on the surface of fresh water ponds and streams, in the deserts of Australia and in the frozen wastes on Antarctica.

In fact they reach a more Southerly distribution than any other hexapod (84º 47’ S.) and can survive temperatures less than –60 C. They are however most abundant in warm damp places, and many live in the leaf litter and or the soil.

Deep Cave Springtails

The species of springtails which live in caves or deep in the leaf litter and/or the soil tend to be white, have a reduced furca and reduced or no eyes. The species that live in more open environments are more coloured and are often very beautiful.

Collembola continue to moult about once a week even after they have reached sexual maturity. They don’t however grow infinitely big and I have no explanation for this obviously energetically expensive procedure. Collembola stand around doing apparently nothing while preparing to moult and have to have an empty gut before moulting.

This is because – like their close relatives the insects – they shed part of the stomach lining with their external skin. Due to this this females loose any sperm they have stored from mating and have to mate again after each moult.

They are generally small and some species of Neelidae are among the smallest hexapods in the world at just over 0.2 mm long. While the largest Collembola are in the family Uchidanuridae which can reach 10 mm in length.

Most species live for a year or less, however some live considerably longer and the record for long life in the laboratory is 67 months for a specimen of Pseudosinella decipiens.

Most Collembola feed on the fungi and bacteria found in rotting organic matter but many arboreal (living in trees) and epidaphic (living on the surface of the soil) species also feed on algae. Some feed on other plant materials and in some places, particularly Australia, Sminthurus viridus is a pest of lucerne crops. A few other species are carnivorous feeding on Nematodes and other Collembola.

Many species of springtails are known to have an aggregated distribution, particularly in the soil and this may be to do with mating. In many species, males deposit a spermatophore on the substrate for the females to find. This is generally held at the top of a thin hair or petiole to keep it off the substrate. In some species the males deposit these wherever they feel like, in others they wait until finding a receptive female and then deposit some nearby.

Reproduction

In some species, competing males will eat each others spermatophores before setting up their own in the same place. Other species such as Bourletiella hortensis are more conventional and go in for courtship before the male makes a spermatophore available for the female. In Sphaeridia pumilis, the male uses his third pair of legs to transfer a drop of sperm to the female’s genital opening.

The eggs are deposited singly by some species and in large masses, which may be contributed to by a number of females. A female will lay about 90 to 150 eggs during her life, though this also varies with species. The eggs take about a month to hatch at 8 degrees C but are quicker at warmer temperatures. Tomocerus plumbeus eggs hatch in 3-4 day at about 20 degrees C most will live for about a year.

The young go through between 5 and 13 moults before reaching sexual maturity and the time between moults varies with species and temperature, from as little as 3.8 days in Callyntrura chibai at 26 C to 110 days for Gulgastrura reticulosa

Some species are multivoltine (having many generations in a year), particularly in the tropics, while many others are univoltine. However in the Antarctic some species may take up to 4 years per generation. Some species will live for a long time without food; the longest I know of being 18 months for a single specimen on its own.

Collembola Taxonomy

The Collembola are divided into two sub-orders:

- the ‘Arthropleona’ – which are more or less elongate in for with the thoracic and abdominal segments easily separatable; and which are mostly soil dwellers

- the ‘Symphypleona’ – which are generally rounded in body shape with the thoracic and first four abdominal segments fused together; they are seldomly soil dwellers.

Monographs

The feature image at the top of this page was scanned in from the monograph of Lord J. L. Avebury (1832 to 1913). They were all painted for the book by a deaf and dumb artist called A. T. Hollick and though they may not be as accurate as photos, are still very beautiful. Here are a few:

Sorry if the images appear a little off, it took some work to scan and restore them from the original plates. The springtails are an incredibly visually diverse order and their sheer variety can only be appreciated by looking at more amazing collembola images.

Lastly, if you’re interesting in keeping these incredible creatures as pets, you can also see instructions on keeping collembola.

What Next?

Well, perhaps now you’d be interested to learn a little about earwigs.