Millipedes 101: The Many Legged World Of Class Diplopoda

Millipedes (Diplopoda) are relatively common litter and soil animals, that occur in most parts of the world.

The word ‘milli’ is Latin for a thousand and ‘pede’ is for foot – so a millipede ought to be a thousand-footed animal.

However, whoever coined the name was guessing – because although some millipedes have a lot of legs, none have a thousand. The record holder is Illacme plenipes, which has an amazing 750 legs, or 375 pairs.

Millipedes use their legs to push themselves into the soil, leaf litter, or rotting wood; the more legs you have, the more you can push – so it makes sense to have plenty of legs. Millipedes do not need that many body segments though, so the fusing of two segments into one functional unit – whilst maintaining both pairs of legs – allows millipedes to generate a lot of push without becoming impossibly long.

Anyhow, we’ll get into all that. For now, you can use the links below to skip to the relevant part of this page:

Diplopoda Description

Millipedes (Class Diplopoda) all have relatively short antennae with 8 segments.

The millipede mouth is a pretty simple affair. They have a pair of mandibles (which are armed with a few blunt teeth) and a sort of lower jaw-like plate, called a gnathochilarium; this has several buds along each side, which bear the millipede’s taste organs.

Millipede eyes (when they have any) consist of several simple flat lensed ocelli, arranged in a group on the front/side of the head. Generally, they have between 4 and 90 ocelli depending on species; these eyes are not very good really and millipedes are either blind (i.e. those with no eyes) or have poor sight.

Millipedes breath through spiracles along their body; these are situated well under the body, near where the legs are connected. They have 2 pairs of spiracles per segment, or 2 pair per pair of legs.

Millipedes range in size from 2 mm to 300mm in length (see record holders below).

Most of the 10,000 or so named species of millipedes are detritivores or herbivores, but a few species in the Order Callipodida are known to feed on meat given the opportunity. Millipedes have a calcified exoskeleton, i.e. they use calcium to make their exoskeleton hard.

Millipedes are often not noticed by people, particularly in temperate climes where they are small. Also most millipedes are nocturnal. They are, generally speaking, harmless but most species have a series of metathoracic glands which produce a repellent substance – which they can exude when they feel threatened.

In some larger species this fluid can be corrosive and cause blistering of the skin in large doses.

The oldest know fossil millipede is probably Pneumodesmus newmani from the Early Devonian period. Some past millipedes were the largest ever terrestrial invertebrates; some Arthropleura sp. were up to 1.8 metres or 6 feet long and 0.45 metres or 1.6 feet wide.

How Many Legs Does A Millipede Have?

Most millipedes have far less than the record holder Illacme plenipes, normally 100 to 300. Millipedes are distinguished from all other Myriapods because they have two pairs of legs per body segment. This is because each segment is actually two segments fused together. These special segments are called ‘Diplosegments’.

Though it is not visually obvious, millipedes do have a what is called a thorax and an abdomen. The thoracic segments are the 1st 3 body segments; the rest are the abdominal segments.

The 1st thoracic segment is apodous (without legs) and the 2nd and 3rd have only one pair of legs each. In all Millipedes, except the Colobgnatha, the anterior (front) pair of legs on the 4th body segment is also missing.

Hence, if you want to know how many legs a millipede has, you can count the number of body segments, multiply by 4 and subtract 10; unless it is a member of the colobgnatha, in which case you only subtract 8.

Millipede legs have more sections than insect legs: Coxa, Trochanter, Prefemur, Femur, Postfemur, Tibia, Tarsus and a Claw. Each pair of legs have their own individual set of muscles and they move in pairs. Each pair (one on the left and one on the right) move together, and are slightly out of phase with the pair in front and the pair behind.

This is what causes the metachronal wave effect that is so obvious when you are watching a millipede walk.

- Number of named species: about 10,000

- Millipede with the most legs: Illacme plenipes, 375 pairs or 750 legs altogether

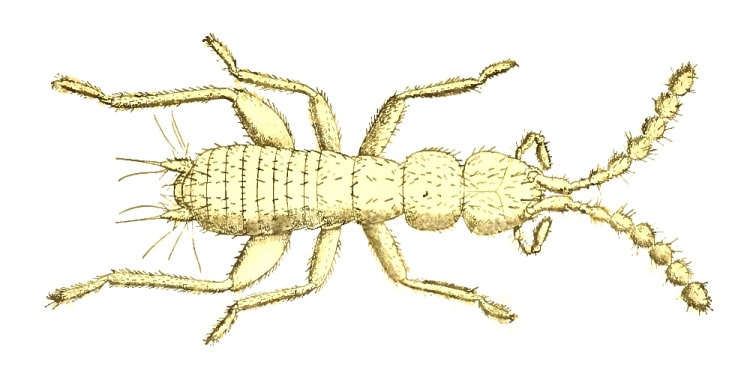

- Millipede with the least legs: Polyxenus lagurus, 12 pairs or 24 legs altogether

- Longest known Millipede ever: Arthropleura sp. were up to 1.8 metres or 6 feet long and 0.45 metres or 1.6 feet wide (though there is some discrepancy about whether they actually were a millipede)

- Longest known living Millipede: Graphidostreptus gigas and Scaphistostreptus seychellarum, both at 28cm or 11 ins

- Shortest known living Millipede: Polyxenus lagurus, 2-3 mm long

- Oldest Fossil Millipede: Kampecaris tuberculata, from Silurian Red Sandstone

- Cave dwelling species: Aragosoma barbieri

- Desert species: Archispirstreptus syriacus and Orthoporus ornatus

- Alpine species: Trimerophorella nivicomes 2,500m above sea level and Trimerophorella niger at 2,800m

- Arboreal species: Tachypodiulus niger (The Fast-footed Black Millipede) and Nemasoma varicorne

- Jumping Millipede: Diopsiulus regressus

- Luminous Millipedes: Mostly in the genus Motyxia (Order Polydesmidae) and mostly from California, e.g., Motyxia sequoiae

Types Of Millipede

Millipedes always look pretty clean… and when healthy, they are in fact very clean animals – spending a great deal of time cleaning and polishing all the various parts of their bodies. They have special, brush-like group of hairs on their 2nd or 3rd pair of legs which are used in cleaning the antennae.

They are also noted for being meticulous about cleaning the gonopods after sex.

There are 4 main types of millipedes in the world, Cylinder Millipedes, Plated Millipedes, Pill Millipedes and Bristly Millipedes.

The long Cylinders can be further divided into Bulldozers (Julids or Iulids) and Borers (Polyzoniida).

Bulldozers are your typical millipede: they are long and thin and use their flattish heads as a bulldozer blade. Their numerous legs supply the oomph, which allows them to push themselves through the soil and leaf-litter.

Borers are the Colobgnatha: smarties called sucking millipedes. They are similar to Julids but have narrow pointed heads, with each successive segment getting slightly larger. They use this shape to winkle themselves into the substrate they are trying to penetrate.

They have small legs which are invisible from above. Colobgnath millipedes have reduced mandibles and likely feed on rotting vegetation; they are also often blind.

Plated millipedes are sometimes known as Wedgers are the Polydesmida. They have the upper plate of each segment expanded out from the centre of the body into a keel or paranota, thus giving them a less rounded appearance.

They work their way into the substrate by wedging in the first plate and then lifting up the body to widen the space; then they push in a little more and lift again.

Pill millipedes are members of either the Glomeridae or the Sphaerotheriida; they are also bulldozers by nature but are better known for their ability to role into a ball.

Bristly millipedes are bark dwellers: they do not burrow and are covered in bristles. They are very small, being only a few mm long; Polyxenus lagurus (2-3mm) is the only British species. These are atypical millipedes and many of the generalisations made in this paper do not apply to them.

Plated millipedes, Pill millipedes and Bristly millipedes all have far fewer segments than the long thin cylinder types.

Distribution And Ecology

Most millipedes live in the leaflitter zone or burrow into the top soil, but some specialise in living under the bark on dead trees or else in rotten wood; some can even be found climbing living trees.

Millipedes are important agents of nutrient fluxes in many habitats. In fact, in some tropical areas they are of more importance than earthworms.

Their main role is one of comminution of plant material, meaning they breakup dead plant material into small pieces – thus increasing the surface area. This is important because the surface is the only part the bacteria and microfungi can reach (and they are the main agents of recycling in the soil).

Millipedes, when they eat rotting vegetation, are really only digesting the fungi and bacteria and the plant material they have already broken down.

An american Biologist called F. H. Colville once calculated that the millipedes. in an un-named forest in USA. contributed 2 tons of manure per acre, per year to the forest floor.

In temperate zones, many species hibernate during winter, i.e. Blaniulus guttulatus (The Spotted Snake Millipede).

In Central America, 3 different genera of millipedes live as symbionts with Army Ants of the genera Labidus and Nomamyrmex. Species such as Calymmodesmus montanus, a polydesmoid millipede, live in the bivouacs during the stationary phase – and travel with the columns when the colony is on the move.

It is theorised by scientists that they may help keep the colony sanitary, by feeding on fungi that attempt to grow within the bivouac; in return they get protection from the ants.

Some species in South America survive flooding by being able to live and breath underwater, by means of a plastron (a plastron is an layer of air that adheres to the body and works as a physical lung, allowing for the transmission of gasses). Species such as Polydemus denticulata can survive at least 75 days underwater.

Our perception of millipedes can be very seasonal; in Natal Africa for instance, the millipede Gymnostreptus pyrocephalus will appear after the first summer rains, appear very abundant for a few weeks and then become very difficult to find again.

Millipede Reproduction

The production of eggs and sperm is achieved in organs called ‘Gonopores’, associated with the second pair of legs; which, as the first segment is always apodous (without legs) and the second only has one pair of legs, is the 3rd body segment.

In some species, i.e Glomeris marginata, males and females are brought together by means of pheromones emitted by the male; but it is generally considered that these are not effective over anything but very small distances.

Before mating, in nearly all species, the male millipede has to charge his secondary sexual organs from his primary ones. To do this, he has to curl his body forward so the spermatophore from his Gonopores on the 3rd body segment can be transferred to his Gonopods (means ‘sex-legs’) on the 7th body segment.

Millipede’s courtship involves the male walking along the female’s back and stimulating her with rhythmic pulses of his legs.

When the female raises her front segments, the male entwines his body around her and – when their genitalia are opposed – sperm transfer occurs. The sperm is passed to the female as a packet called a spermatophore.

The ‘Gonopods’, or secondary sexual organs used in the transmission of this spermatophore, vary in shape with different species; this helps stop closely related species form hybridizing. Females can and will mate several times in the Iulid types, but female Polydesmoid types tend to mate only once a season as far as we know.

Females of the larger Iulid species can apparently be damaged, or even killed, by larger males which can force them to bend backwards too far (though I have never seen this happen).

Parthenogenetic reproduction is known from a number of species such as Polyxenus lagurus and Proteroiulus fuscus.

Female millipedes make an underground nest, into which they lay their eggs. The nest is made by excreting soil they have eaten and using their anal folds to shape it as required; either as a nest for a number of eggs, or as a coating for individual eggs i.e. Glomeris balcanica.

Female millipedes may lay as many a 2,000 eggs – but a few hundred is more likely. There is great variation in the number laid within a species, depending on the size and condition of the female.

Some species such as Tachypodoiulus niger are iteroparous, i.e. they can lay more than one lot of eggs and may live for more than one year as a mature adult. Other species such as Ophyiulus pilosus are semelparous, i.e. they lay one batch of eggs and then die.

Growth and Development

Young millipedes hatch inside the nest and remain within it. They then rapidly, usually within 12 hours, moult again into their first stadia (instar). Polydesmus inconstans leaves the nest after this, but other species remain in the nest for up to the first three stadia i.e. Pachybolus ligulatus.

Some species even build a special moulting chamber.

There are numerous variations on this theme, for instance Orthomorpha gracilis remains inside the egg during its first stadium – and does not hatch until after it has moulted to stadia 2. Stadia one millipedes have 3 pairs of legs on segments 2, 3 and 4; except in some Colobgnath species such as Polyzonium germanicum, which has 4 pairs.

However, they gain legs rapidly with each moult; the first young millipedes you see are normally already in possession of quite a few legs.

Temperate species tend to eat about 5X their weight in leaf litter between hatching and reaching maturity. They digest some of the plant material themselves, particularly any proteins and simple sugars. They also digest some of the micro-organisms that inhabit the surfaces of the material, particularly the fungi.

Micro-organisms play a crucial role in the digestion of Millipedes, by breaking down the cellulose that makes up the plant fibers into more smaller and easily digestible molecules like simple sugars.

Many millipedes indulge in coprophagy, i.e. they eat their own faeces. Some species, such as Apheloria montana, will die if not allowed to feed on their own faeces – quite why is not fully understood.

Again, the main nutrient gain is the result of microbial activity and not a result of the millipede’s better digestion of the plant material the second time around. It is important to remember that many animals which feed on plant material have relatively inefficient digestion. Cow dung for instance contains a large amount of finely chopped, but still recognisable, particles of grass.

Temperate species take as much as 3 years to reach maturity and may live for several more; but the larger tropical species can take as long as 10 years to reach maturity – and live for several years as an adult.

Moulting is a dangerous time for any arthropod and many millipedes build themselves a special chamber of faecal soil, similar to the egg chamber, in which to moult. Others use only a simple depression in the ground, or a natural hide-away such as an empty seed pod. Millipedes need to moult many times because their skeleton is very inflexible; some species spend as much as 10% of their life moulting.

Millipede Predators and Parasites

Predators: many mammals are predators of millipedes including Elephant shrews, Water shrews and Hedgehogs, Cape Dormice and Mongoose. They are also eaten by Frogs, Lizards, Tortoises and Birds such as Francolins, Guinea Fowl, Herons and various Robins to name just a few.

Other invertebrates such as Reduviid Bugs, Scorpions, Carabid Beetles and Staphylinid Beetles will eat millipedes, as will a few species of Ants. Though most ants tend to leave millipedes alone.

Parasites: millipedes are prey to a number of parasites such as Fungi, Protozoa, Nematoda, and Acanthocephalan worms. However, the best studied millipede parasite is Sciomyzid fly. Pelidnoptera nigripennis is a parasite of Ommatoiulus moreleti, which is a pest species in Australia where it has been introduced from Europe.

Many millipedes are seen with mites running over them; the general consensus of opinion is that these are mostly, if not all, phoretic mites (just hitching a ride) and are not harming the millipede.

Defense

The reason so many animals (most ants and spiders for instance) do not eat millipedes, is that they have a series of defensive glands along both sides of their body. This does not apply to the Sphaerotheriida, Chordeumatida and the Penicillata.

These glands give off defensive secretions of varying sorts, that are generally foul tasting and sometimes either poisonous or sedative.

The defensive fluids of Glomerids tend to contain quinazolinones, glomerin and homoglomerin. Iulids and the other cylindrical millipedes use a wide range of substances including benzoquinones and aliphatic compounds i.e Narceus annularis has toluquinone 2-methoxy-3-methyl-benzoquinone as its main ingredients.

Polydesmids, or plated millipedes, use Cyanide compounds; which they store as a harmless precursor molecule (such as mandelonitrile) and which is released in conjunction with an enzyme that breaks it down to Hydrogen Cyanide and Benzaldehyde.

Millipedes as Pests

Millipedes occasionally exhibit population explosions in a huge way. Parafontaria laminata in Japan becomes so numerous on occasions, that they stop trains by causing the wheels to loose traction.

Masses of millipedes have also been reported as stopping trains in Germany, France and Hungary. In West Virginia USA in 1949, one swarm of millipedes is estimated to have been made up of 65 million individuals.

Millipedes are generally considered to be harmless, but they can be pests in some circumstances. In Europe, sugar beet is the main crop to suffer from millipedes. In Africa, Spirostreptids can be damaging to cotton and groundnuts.

Blaniulus guttulata, the Snake-spotted Millipede, accounts for most of the complaints against millipedes (these averaged about 20 per year in 1940); while in America Oxidus gracilis (Greenhouse Millipede) is the main culprit. In Australia, Ommatoiulus moreleti (which was introduced in 1953) is a pest of crops and a nuisance in houses – which it invades at night because it is positively phototactic (attracted to light) in areas where it occurs.

Stranger still, the millipede Orthomorpha gracilis, a species now much spread around the world in greenhouses, is/was once a pest in the gold mines of Johannesburg South Africa – where it eats/ate the wooden pit-props, thousands of feet below the ground.

Diplopoda Taxonomy and Classification

Class Diplopoda

Subclass Pencillata

- Order Polyxenida

Subclass Chilognatha

Infraclass Pentazonia

- Order Glomeridesmida

- Order Sphaerotheriida

- Order Glomerida

Infraclass Helminthomorpha

- Order Siphoniulida

Subterclass Colobognatha

- Order Platydesmida

- Order Polyzoniida

Subterclass Eugnatha

Superorder Nematophora

- Order Stemmiulida

- Order Callipodida

- Order Chordeumatida

Superorder Merocheta

- Order Polydesmida

Superorder Juliformia

- Order Spirobolida

- Order Spirostreptida

- Order Julida

What Next?

Well, I hope this page has given you an interesting glimpse into the wonders of class Diplopoda.

Did you know a pet millipede makes a great addition to your household?

Illacme plenipes (credit: Marek, P.; Shear, W.; Bond, J.) Image License: Creative Commons

Graphidostreptus gigas (credit: Guérin Nicolas) Image License: Attribution Share Alike

Do you mind if I quote a couple off your articles as

long as I provide credit and sources back to your blog? My blog iss in the exact same area of interest as yours and my visitors

would certainly benefit from some of the information you

provide here. Pleazse let me know if this okay with you.

Many thanks!

Please go for it. All the best.

nice introduction. Do you have any information on overwintering in cooler climates. Do they hibernate in the upper soil zones or do the move lower in the soil profile as temperatures cool in the fall; moving back up in the spring. if they do move with temperature, how far can they move; a few inches or can they move several feet.

Thank you

A complex set of questions Terry. The answer is no, I do not have such information to hand, but in our modern world there are a lot of scientific papers available on line, you never no what you might find.